A recent study published out of The University of East Anglia has shown – what many have long suspected - that the human brain treats well designed tools (like a spoon or a hammer) as an extension of the human body. More importantly, this study shows us that well-designed tools are interpreted by the brain differently than poorly designed tools which the brain simply treats as an external object. For more context, this Twitter thread does a good job of summarizing the study’s findings.

To understand the implications of this insight we can look to history.

History teaches us that tools and systems with consistency, quickness, and interactivity can be more easily mastered, and this tool mastery leads to psychological flow states of consciousness that can bring about rapid change.

This insight is relevant to our current moment because what I am seeing in the world of business data & analytics is a never-ending tension between tools that users love and can produce great outcomes, and inferior tools which users are forced to use out because of vendor lock-in homogeneous architecture constraints. I will return to this theme in an upcoming article (Part 3 of my Analytical Efficiency series), but in this article will explore this topic head-on.

How does history teach us about tools and mastery?

Let me tell you some stories …

During my undergrad years at university in the early-mid 1990s – majoring in Computer Science – the computer workstations we were provisioned all ran on a UNIX based OS (Solaris). Whether you used one of the newer “X-Window” terminals or one of the older text-based terminals you would have to learn one of the command lines and associated text editor.

I recall being quite frustrated by this at first. I had my own PC, an 80386 SX. While I could use this PC for preparing assignments in WordPerfect - a popular “WYSIWYG” (‘What you see is what you get’) word processor at the time - I could not use my home PC for preparing computer science work (i.e. writing code) because I needed to have access to shared tools and datasets. Since all the Comp Sci workstations ran on Solaris I was suggested by a UNIX-savvy peer to use a text editor called “VI” (an abbreviation of “visual”).

Using VI at first felt like psychological torture. There was nothing intuitive about it mainly because VI requires the user to toggle between two modes: “Insert mode” where you can freely enter text as you would do normally; and “command mode” which is a bit trickier to explain but as its name implies allows you to navigate and manipulate blocks of text using keyboard commands with ability to program new commands. Many of the commands in “command mode” are activated by hitting a single character on your keyboard and the most commonly used commands (for scrolling through the text) were characters on the home keys themselves. For example: ‘j’ moves the cursor up a line and ‘k’ moves you down, while ‘h’ moves the cursor left and ‘l’ moves right.

Over time I became more proficient with “VI” and found that I could work much efficiently than the old Borland IDE text editor I had been using before. But what about my other subjects? What about WordPerfect?

By 2nd or 3rd year a friend showed me how he prepared all his essays using “VI” but compiled them into PostScript files which could then be printed out and handed in. To do this I had to use another tool called “LaTeX”. This tool was a compiler for a markup language called “TeX” which is like HTML but is more of a typesetting system with precision around page layout. In other words, a possible replacement for WordPerfect. But this also required learning LaTeX and TeX which I never mastered but did learn enough of what I needed like font changes, indented paragraphs, tables, number lists, bullet lists, and so forth. On top of this I would also borrow “code” from others to add more impressive flourishes. I also followed my friend’s advice and created a little “makefile” which I used to compile my LaTeX files into PostScript files that I could view before printing which adequately compensated for the lack of WYSIWYG functionality and provided quick feedback.

By the end of my final year in university I was able to write and edit term papers using “VI” faster than I could in WordPerfect while at the same time the quality of the printed page looked like it had come from a professional publisher.

Today, I still use “VI” occasionally, but not for word processing – formats like “LaTeX” are too obscure for the business world and Microsoft Office (or compatible copycats) are the order of the day now. I don’t have a big problem with this, but there is a part of me that yearns for that feeling of mastery I once felt when editing text. It’s probably the reason I do use “VI” when I can – it’s not just more efficient, it feels good.

George R. R. Martin, author of the Game of Thrones series apparently also feels good when using older and simpler tech like “VI” except in his case he uses another tool called WordStar. WordStar is an older word processor that only runs on MS-DOS and has not been updated since the 1990s. Like “VI” it is oriented around the keyboard and home keys in particular making it easy to navigate and manipulate a document without taking your hands off the keyboard. I heard from this podcast episode that Robert Sawyer – a popular science fiction writer- also uses WordStar for the same reason. Namely, he prefers a tool that minimizes friction between the thoughts in his head and the words that get put down. By using a streamlined tool like WordStar, Sawyer explains that he can more easily keep his train of thought and remain “in the zone” while writing.

What Sawyer is referring to is known as the “flow state” and is now generally regarded to be the ideal state of human performance when we are both happiest and most masterful in our work. If you have ever biked, skateboarded, or skied down a big hill you will know this feeling.

Why then is it that tools like MS Word (which Sawyer eschews in favour of WordStar) do not work like WordStar? Robert Sawyer’s specific answer to this question is that MS Word did not evolve around writers and creatives but rather the main users of the tool are secretaries and assistants who appreciate the extra features that allow them to perform advanced typesetting and other sophisticated tasks with relatively little training.

In other words, the professional writers depend on tool consistency – even if there are fewer features – since mastery is of writing itself is paramount. Executive assistants and other staff involved in document preparation are less concerned with the content of writing itself and rather the formatting, presentation, and distribution of documents – something modern word processors like MS Word are replete with.

This tension between tools like VI and WordStar suited for power users versus tools like WordPerfect and MS Word for more casual users.

As a side-note many creative writers often use another tool called “Scrivener” which is more purpose built for story writing (e.g. there are features to keep track of plots and characters) than say MS Word, but I wouldn’t be surprised if folks George R. R. Martin stick to Wordstar for the simple reason that they can wield it with more efficiency.

A user-friendly tool can spread quickly and aids efficiency. But occasionally in history we see other tools appear that are not so user-friendly but when mastered can change the world.

An example that comes mind is the horse. A horse being an animal is not normally thought of as technology. Starting in the bronze age around 5,000 years ago horses domesticated on the Eurasian Steppe led to massive waves of migration and change – it is why so many languages fall under the umbrella of “Indo-European”. To get a clearer picture of what made the horse such a formidable tool and why it remained such a powerful tool on the Eurasian Steppe for so long I want to point out a few things about Genghis Kahn’s Mongol Empire during the 13th century.

The Mongolian horse differed from the stockier European horse – like those horses The Normans favoured. Similar to the Mongol’s, the Norman’s were also known for striking fear through their armoured knights and horses who were not only large and powerful but had been bred for combat and could not be easily spooked.

The Mongolian horse on the other hand was smaller and not as powerful as the Norman’s European horse. But the Mongolian horse did have some advantages: The European horse required grain feed in order to thrive which made it more expensive to feed. This meant that the European horse also needed to be on or near a farm where the grain could be supplied. During times of war the European horse was highly effective in the battlefield but was expensive and challenging to maintain because keeping supply lines safe was crucial for success due to the horse’s dependence on grain from farms. On the other hand, the Mongolian horse could feed off the grass in the steppe or any meadow. Even during winter, the Mongolian horse can punch through a top layer of frost and ice to get at the grass (unlike cows which could not penetrate the frost and would starve). A Mongolian soldier did not need to worry about supply lines for the horses and would have additional horses (each soldier usually kept four horses) that could be eaten if necessary. This provided more agility during times of war.

Because of this self-contained sustainability of the Mongolian horse in conjunction with the grass food source the steppe provides, the main advantage of the Mongolian horse is that it allowed for a nomadic/itinerant culture to sustain itself through a very horse-centric lifestyle. If you are born into a nomadic horse culture then it is said you are “born on the saddle”. In other words, through the consistency of being able to take horses anywhere and everywhere, the mounted archer quickly develops mastery and can take their mastery to higher levels than a European soldier whose experience with horses would be more sporadic. This is the true power of all great steppe cultures including the Xiongnu and Scythians that came before the Mongols (even perhaps as far back as the late 4th millennia BCE during the bronze age when the Yamnaya culture spread out from the Pontic-Caspian Steppe and seeded all Indo-European cultures). Growing up as a steppe nomad like a Mongol you would begin as a mounted archer as young as 5 or 6 years old, or maybe younger. A child would then start on a sheep with a small bow and hunt small animals like rabbits and squirrels. Once they get into their early teens they move to a slightly larger bow on a small horse and begin hunting larger animals like foxes. Once adulthood is achieved the grown adult moves on to a full-grown Mongolian horse with the full composite bow and begins hunting large game like deer. The Mongolians would also play these “encircling” games on horseback whereby a group of mounted archers cooperates to form huge circles – as large as 10 kilometres in diameter and then begin to spiral and close the circle by herding the animals towards its centre eventually trapping all the animals in the middle. As is now well known these mounted archers could punch far above their weight and inflicted great terror during their raids which eventually allowed them to form empires like the Mongolian and Kahn Empires which at the time was the largest empire ever formed.

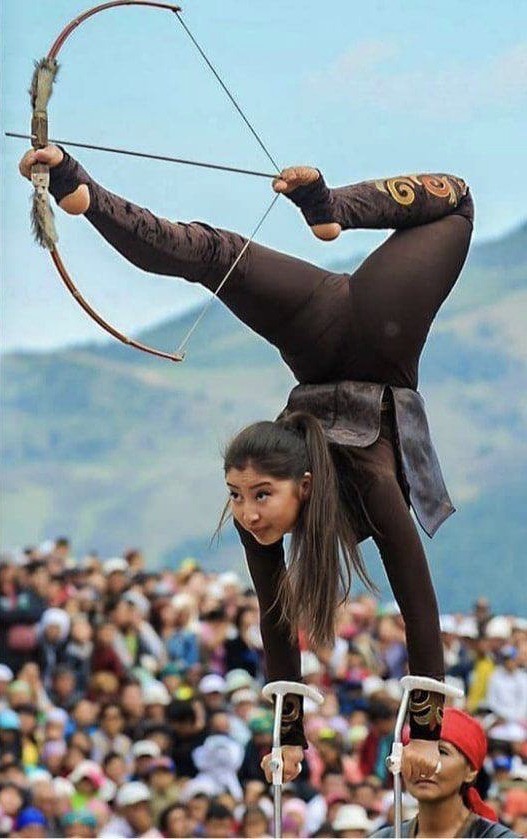

Women also played a key role in these steppe nomad cultures since the horse was very much a leveler of human strength, like the gun is today (which is also why gunpowder eventually displaced horses as the primary war technology). Those “Amazonian women” you may have heard about - possibly through the classical that the Greeks who wrote about them or maybe you saw the Wonder Woman movie - were likely Scythian steppe warrior women who were mounted archer warriors that were part of a much older tradition that goes back to the bronze age. In the Xiongnu culture (predecessors to the Mongols), women routinely held the highest status often more so than men which we know from the items they were buried with (they prized large ornate belt buckles), starkly in contrast to neighbouring civilizations at the time. Technology with consistency can be a great equalizer too.

[An acrobatic archer competing in the World Nomad Games]

The word “Centaur” – the Greek mythological half-person half-horse creature - comes to mind here.

Centaur is also the word used to describe “Advanced Chess” players. What is Advanced Chess? Advanced Chess was invented by chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov after losing to Deep Blue, a supercomputer developed by IBM. Advanced Chess allows humans to use computers to aid their decision making (e.g. by testing out a move to see what may happen) but do not rely entirely on the computer’s judgement. This allows the human player to focus on higher order strategy while reducing accidental errors. Centaurs tend to beat both humans (without computers) and computers (without humans) at chess.

These improved chess results are in large part because the human can consistently focus on strategy, as opposed to checking for errors or flaws. The thought process becomes more consistent and more efficient.

New user-friendly tools that can be used by many and spread far and quickly and change people and by extension change the world, like how the horse and text editors/word processors changed the world through their very transmission. Over time tools begin to accrete additional features and functions. These extras can be useful for certain scenarios, but when they clutter the original purpose, they can sometimes undermine mastery. Other times if the tool has been extended that does not disrupt the consistency of the original experience then the changes are usually welcomed.

In conclusion, tools that are highly consistent, quick, and interactive in their usage that allow for a wide range of possibilities for the user can be more easily mastered than tools which may have more features but are less consistent in how those features are put together. It is primarily through this consistency that one can achieve mastery and through mastery that one can achieve a flow state of consciousness. And let us not forget that flow states are most often associated with happiness and contentment up there with spending time with friends and family.

This is the reason people love their favourite tools.

Postscript: History is messy, and no analogy is perfect, but analogies are useful and should not always be thrown out due to a perceived contradiction. In that spirit, here are some details I left out that add colour and do not directly contradict my argument, but could be taken out of context to confuse some readers:

- I am using the word ‘nomadic’ to refer to an itinerant agro-pastoralist migration pattern as opposed to the more random wandering pattern that the early hunter-gatherers exhibited

- Although the Mongols did dominate through their mastery of horses and archery, the horse was not the only piece of defining technology; The invention of stirrups which provides stability for mounted archers and the invention of the composite bow allowed for a smaller bow to produce more power were also part of this “mounted archer” package. Furthermore, the defining feature of Genghis Kahn’s Mongolian empire (in contrast to other steppe nomads) was his ability to federate large numbers of disparate tribes and cultures for a common goal, and leverage that diversity to incorporate state-of-the art warcraft like siege technology

- Although the Norman’s were feared in large part because of their superior cavalry it must be pointed out that the most famous and iconic Norman battle of all – The Battle of Hastings – was decided more through circumstance and chance than by cavalry: The English succumbed to a one-two-punch knock-out blow, first from Viking Norwegian invaders led by Harald in the north - who were defeated in the Battle of Fulford - quickly followed by a separate Norman invasion led by William in the south that converged at Hastings. But perhaps this is in line with my original point – the Normans lacked the mastery of the Mongols when it came to horses

- Technologically, mounted archers “born on the saddle” were not new: The Xiongnu - possible ancestors of the Huns - also formed a large empire centuries earlier using the power of mounted archers “born on the saddle” and like Genghis Kahn had also federated tribes – but had got caught up in a civil war. Like the Mongols, the Xiongnu and Huns were highly disruptive and nearly brought down the Han Dynasty and Roman Empire, respectively. However, the reputation of the Mongols is better known these days and thus why I am using the Mongol example to illustrate the overwhelming power of mounted archers “born on the saddle” and how technology when fitted properly to humans can have highly disruptive consequences in a very short period of time.

No comments:

Post a Comment